October 18, 2021

50 VPN Statistics & Key Trends [2022]

This year alone, VPN usage has increased drastically, many services have vastly improved, and the [...]

WHAT’S IN THIS REVIEW?

Disclaimer: Partnerships & affiliate links help us create better content. Learn how.

Transparency is often used as a buzzword in an attempt to make companies seem like they’re slightly more open and accountable. It’s rare to see in practice, especially when it comes to the murky world of VPNs. It goes beyond a provider’s location and ownership, but those two aspects are still the first telltale signs of trustworthiness that are always worth checking before you commit to handing over your personal data.

Here’s everything you need to know about transparency, VPNs, and why their ownership matters.

In terms of business, transparency involves operating in a non-secretive manner, making it easy for others to see what you’ve been up to. It’s not a default position for many companies, especially as it can get in the way of making a profit.

Transparency also isn’t especially important for the average consumer if you take into account a Techradar survey, which found that only “8.7% of readers cited transparency as their number one concern” when buying a VPN. You’d think it’d be a top factor.

Users in this survey were more interested in aspects such as security and privacy, which is fair. However, transparency is key to understanding whether a VPN’s logging claims can actually be trusted. It also serves to give you a better idea of a company and its practices, so you won’t have to take their word for it.

Consider UFO VPN, a Hong-Kong based provider that claims to have a strict no-logs policy.

In July 2020, they accidentally exposed a database of user information, compromising up to 20 million accounts in the process. Comparitech’s Bob Diachenko found that the leak included:

They shouldn’t have had the information in the first place according to their own privacy policy, and it’s bad news for anyone who was affected. (At the very least, they’ll need to change any reused passwords to be on the safe side.) The point is a privacy policy might say one thing, but it means little without a third-party audit to inspect a VPN’s procedures and the hardware itself.

UFO VPN is far from the first company to be caught leaking user data, despite advertising no-log claims within their privacy policy. But we’re interested in how they went about addressing the issue. UFO VPN blamed the coronavirus outbreak for the data leak, rather than accepting responsibility for their misleading privacy policy. They said:

“Due to personnel changes caused by COVID-19, we’ve found bugs in server firewall rules immediately, which will lead to the potential risk of being hacked, and now it has been fixed.”

Compare and contrast that with Windscribe, whose founder Yegor Sak released a preemptive statement following the seizure of two servers located in Ukraine, which were found to be unencrypted:

“We make no excuses for this omission. Security measures that should have been in place were not. After conducting a threat assessment we feel that the way this was handled and described in our article was the best move forward. It affected the fewest users possible while transparently addressing the unlikely hypothetical scenario that results from the seizure.”

Primarily, VPNs are used to keep personal data safe, while adding a layer of privacy and anonymity when online. Transparency is a great method to give peace of mind to the average user since any potential flaws or conflicts of interest should be easily identifiable.

Almost every VPN has faced problems in the past, and you’ll be able to tell a lot about a company when studying the way they deal with letting their customers know about it.

In most cases, a VPN location doesn’t really matter, especially in a world that is getting smaller with the rise of online services.

For example, despite being based in the UK, my bank is in Hong Kong, my phone was made in China, and I regularly watch shows on US apps like Netflix. However, some regions are far safer than others if you’re using a VPN to provide anonymity.

March 2021 was the 75th anniversary of the formal partnership between UK’s GCHQ and the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA), also known as the UKUSA agreement. Formed during the First World War, the countries eventually agreed to post-war communications intelligence cooperation. Canada joined UKUSA in 1949, while Australia and New Zealand were added in 1956. Together, they form the 5 Eyes Alliance, which is still in effect today.

The intelligence-sharing arrangement is one of the main reasons why security experts advise avoiding any of the countries listed above when choosing where to HQ a VPN location. The alliance has also been expanded to include a number of European countries, listed as follows:

Remember, if a VPN is owned by an umbrella company, they’re going to be subject to the laws of their region, and providers will be compelled to give up any data they do have. It’s also worth noting that the Snowden files made multiple references to the NSA having VPN access, as well as the US government unsuccessfully requesting backdoor keys from Apple to bypass iPhone encryption in 2016.

That’s why NordVPN is based in Panama, and any serious provider tends to stay away from the US and the UK especially. They’ll do their best to get their hands on that data, one way or another.

In and of itself, there’s nothing wrong with owning multiple VPN services. After all, it’s a good way to claim a larger share of the online security market, and you can offer something slightly different each time, such as accounting for users with lower/higher budgets or alternative regions. However, it’s slightly unethical if your VPNs are in direct competition with one another, or they make no mention of the umbrella company that owns them all.

Then there’s the possibility of a conflict of interest. Do any of the VPNs share resources, such as server locations or developers? Could the owner be selling the same VPN twice, ever so slightly reskinned so they don’t draw attention to the fact?

Here are some of the companies that own multiple VPN services:

ActMobile Networks appears to be based in the US according to the address listed at the bottom of their main page: 1070 Gray Fox Circle Pleasanton, CA 94566, USA. However, their business address is a residential property, and they have one of the emptiest privacy policies I’ve ever laid eyes on. It appears as though their India headquarters does a lot of the work, according to active roles on LinkedIn.

AnchorFree has been around since 2005, making good use of a freemium model to attract millions of customers. They were named in a complaint by the Center for Democracy & Technology (CDT) in 2017, for the “undisclosed and unclear data sharing and traffic redirection occurring in Hotspot Shield Free VPN that should be considered unfair and deceptive trade practices under Section 5 of the FTC Act.” The company is headquartered in Redwood City, California, with further offices in Ukraine and Russia.

Avast previously owned four competing VPN services before they recently merged with Norton in a deal worth more than $8 billion. They’re now one of the largest players in the online security sector. Norton is the buyer, and they operate out of Mountain View, California.

Innovative Connecting is based in Singapore. Their services have names such as Unlimited Free VPN Monster, but that hasn’t stopped them from being downloaded and used by millions of customers who are desperate for a solution that is free of charge. Unfortunately, the rest of their VPNs have been reviewed poorly, which makes sense as we’d be especially wary of any “‘free” apps that seem too good to be true. In this space, you really get what you do–or don’t–pay for.

Kape is a cybersecurity company that claims to focus on enhancing consumers’ digital experience around the world with greater privacy and protection. In practice, they own a trio of competing providers and recently purchased Webselenese in March 2021.

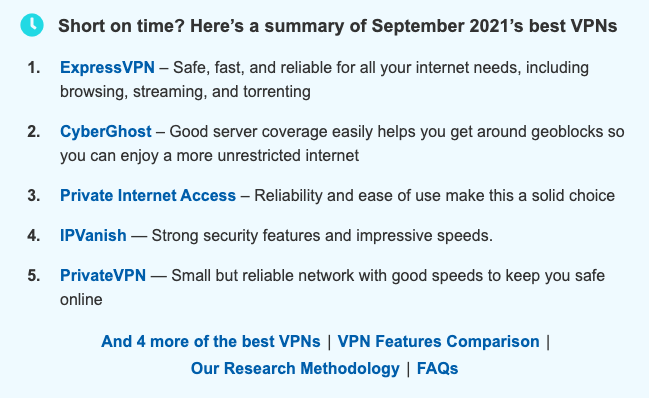

Why does this matter? Webselenese runs the review site vpnMentor, which is a conflict of interest, even if they strive for editorial independence. For example, here’s vpnMentor’s summary of September 2021’s best VPNs, which also happens to include two of the three services under the Kape umbrella:

They may be the best options, but the average consumer won’t make the connection between PIA/CyberGhost and vpnMentor.

J2 Global owns a number of reputable internet information services including IGN, Mashable, Humble Bundle, Speedtest, PCMag, RetailMeNot, Offers.com, Spiceworks, Ekahau, Everyday Health, BabyCenter, and What To Expect as part of their extensive digital media portfolio. In a similar vein, they own five reasonably well-known VPN providers, with IPVanish being the jewel in the crown. The potential conflict of interest is obvious, while PCMag has the following disclaimer for VPN content:

Once again, it’s not a great look when companies review VPNs while sharing ownership with said VPNs. However, of the lot, IPVanish and StrongVPN are two VPNs I’ve reviewed myself and can vouch for. In fact, I’m connected to a UK IPVanish server as I write.

What should you be aiming for with a transparent VPN provider? And how secure is a VPN, really? There are a number of things to look out for when making up your mind.

NordVPN (Panama), and ProtonVPN (Switzerland) are two secure VPN examples that come to mind, with both based outside of 5-eyes/9-eyes/14-eyes jurisdiction. They’re not affiliated with any other brands, and they score highly in terms of personal security.

Speaking of transparency, NordVPN recently completed an advanced application security audit performed by VerSprite. And, all ProtonVPN apps are open source and audited. They’re independently owned and operated, and tick every box mentioned above.

At the end of the day, you want to know – are VPNs safe? How transparent a company is about their business says a lot about whether or not they are.

Transparency, VPN location, and ownership all tie into each other, especially when trying to gauge the trustworthiness of a specific VPN service. After all, just because a company claims to be a no logs VPN service doesn’t mean that they aren’t keeping tabs on their users in some shape or form.

With so many competing providers, it’s tough to know who’s telling the truth, especially when some VPNs have sister sites that are supposed to provide impartial opinions within the industry. It’s understandable given the size of the sector. According to Statista data firm, the VPN market was a $23.6 billion industry in 2019 and is due to reach $35.73 billion in 2022. That’s a lot of money when all is said and done.

On the other hand, owning more than one VPN isn’t necessarily a bad thing, especially if they’re open and honest about the situation. Identifying a VPN’s HQ and real ownership might take some research, but it’s worth the time and effort if you’re unconvinced by a service.

There are still a number of viable independent options such as NordVPN or ProtonVPN, and it’s probably a better move to check them out rather than giving more money to one of the giants mentioned at the beginning of this page, who will probably continue to buy competing services long-term.

Every time they buy up another VPN, the landscape gets ever so slightly smaller, which probably isn’t a good thing when anonymity and security are so important.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __cfduid | 1 month | The cookie is used by cdn services like CloudFlare to identify individual clients behind a shared IP address and apply security settings on a per-client basis. It does not correspond to any user ID in the web application and does not store any personally identifiable information. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-analytics | 1 year | This cookies is set by GDPR Cookie Consent WordPress Plugin. The cookie is used to remember the user consent for the cookies under the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-non-necessary | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Non-necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 1 year | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 1 year | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-functional | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-others | 1 year | No description |